Literary Realism Essay

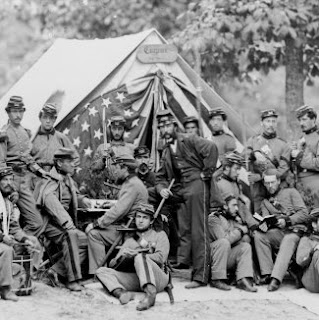

The Civil War was one of the catalysts for the Realism literary movement. The armed conflict brought disillusionment to the country. Not only were Americans fighting their fellow citizens, but photography brought graphic images of death and disfigurement to the public. It comes as no surprise, then, that writers of this era would use the Civil War as a principle theme in their stories. Ambrose Bierce did so in “Chickamauga,” regarded as one of his finest pieces of literature. The lasting impact of death and emotional disillusionment contrasts mightily with more “romantic” views of war: nobility, patriotism, glory, etc. Hamlin Garland’s “The Return of a Private,” uses realistic elements in his story to accurately depict circumstances of the Civil War.

The Civil War was one of the catalysts for the Realism literary movement. The armed conflict brought disillusionment to the country. Not only were Americans fighting their fellow citizens, but photography brought graphic images of death and disfigurement to the public. It comes as no surprise, then, that writers of this era would use the Civil War as a principle theme in their stories. Ambrose Bierce did so in “Chickamauga,” regarded as one of his finest pieces of literature. The lasting impact of death and emotional disillusionment contrasts mightily with more “romantic” views of war: nobility, patriotism, glory, etc. Hamlin Garland’s “The Return of a Private,” uses realistic elements in his story to accurately depict circumstances of the Civil War.

The story begins as a group of Union soldiers return via train to La Crosse, Wisconsin. The third-person narration describes the elation of the returning soldiers upon arriving home. “When they entered on Wisconsin territory they gave a cheer, and another when they reached Madison, but after that they sank into a dumb expectancy” (185). Here, Garland confronts the reader with the conflicting emotions of the soldier’s return. On one hand, they feel a strong sense of elation as their train nears their ultimate destination, from which their cheers derive. On the other hand, there is this “dumb expectancy.” A more colloquial understanding of dumb is a lack of intelligence. However, dumb can also mean silence, or a temporary inability to speak. Most soldiers were away from home for years. Being alienated from loved ones causes natural gaps in emotional inter-connectivity. This can cause a sense of apprehension for returning soldiers. This conflicting, grappling of emotions is a very “realistic” element. Instead of focusing on more romantic ideals of soldiers when they arrive home, Garland admits to undoubted nervousness and anxiety.

Garland also describes the physical detriments these soldiers have undergone. “Three of them were gaunt and brown, the fourth…gaunt and pale, with signs of fever…One had a great scar down his temple, one limped, and they all had unnaturally large, bright eyes, showing emaciation” (186). These are not descriptions of Romantic characteristics. These conditions are extraordinarily “real,” void of sentimental dillusion.

Garland also confronts the reader with another rebuke of Romantic ideology. When modern readers consider the notion of returning, victorious soldiers, images of ticker-tape parades and a famous photograph of a sailor kissing a strange woman in the midst of celebration in New York’s Time Square can easily come to mind. This is a classic image of admiration in post-victorious warfare. Although this example comes far after the Civil War, it nonetheless illustrates a prevailing assumption of the “glory” of war, and the adulation of the adoring populous.

“There were no bands greeting them at the station, no banks of gaily dressed ladies waving handkerchiefs and shouting ‘Bravo!’ as they came in on the caboose of a freight train into the towns that had cheered and blared at them on their way to war” (186). Garland’s story does not include the vocal adoration so prominent in one’s romantic conscience.

One of the most successful government programs in this country’s history was the G.I. Bill of the 1950’s. Returning war veterans were able to go to college, buy homes with discounted loan rates, and could receive generous unemployment benefits should they need it. However, after the Civil War, there were no programs of that magnitude. It appears, after service in the armed forces, soldiers would return home to face the same economic conditions that they left. Garland includes this accurate condition as it, presumably, would play-out in the mid-West. “All of the group were farmers…and all were poor” (186). Many of the soldiers in the story with responsibilities toward their families could not afford a night stay at a hotel before the venturing home the next day. Private Smith, the story’s protagonist, states, “‘Now I isn’t got no two dollars to waste on a hotel. I’ve got a wife and children, so I’m goin’ to roost on a bench and take the cost of a bed out on my hide’” (186). Another soldier affirms, “‘Hide’ll grow on again, dollars’ll come hard. It’s goin’ to be a mighty hot skirmishin’ to find a dollar these days’” (186). Private Smith later contemplates the conditions in which he finds himself. “He saw himself sick, worn out, taking up the work on his half-cleared farm, the inevitable mortgage standing ready with open jaw to swallow half his earnings. He had given three years of his life for a mere pittance of pay, and now!—” (187). Hardly the ideal soldier’s return home.

The pieces of dialogue quoted above exemplify another characteristic of the Realism movement. Very often, Romantic writers would use proper or “enlightened” language in their discourse. In “The Editor’s Study,” 1887, William Dean Howells wrote “…each new artist, will be considered…in his relation to the human nature” (258, emphasis mine). The essential point that Howells, and other Realists, made was that it is detriment that authors create stories and characters that authentically represent people as a whole. The enlightened language of the Romantics was no longer sufficient, in their opinion, because they were so inauthentic. The dialogue exchange between the soldiers in the story is far more justifiable to a Realist. A Romantic writer might shudder to use “natcher’l” as a phonetic depiction of the word natural by one of their characters, as Garland does (187).

Prolonged dislocation from one’s home implies a separation from the realities surrounding that home prior to leaving. Essentially, one would like their home to remain the same throughout their time away. This is more of a romantic desire (although one that’s not easy to remove from one’s thoughts and imagination, even for the most staunch of Realists). It is not unheard of for any soldier to contemplate fondly on, say, their wife’s geraniums in the backyard, the smell of honeysuckle trees scattered around one’s neighborhood, even the smell of grass and dirt at their nephew’s Little League baseball field. These memories of one’s home nourish hope and help dissipate loneliness. However, upon return one can find geraniums uprooted, honeysuckle trees dead, and baseball fields abandoned to the elements.

Garland illustrates such a point with Private Smith. After arriving in La Crosse, Smith imagines the reaction of his family at his long-hoped return. He imagines returning home late, catching his sons milking the cows long after the preferred time. “‘I’ll step into the barn, an’ then I’ll say: ‘Heah! why ain’t this milkin’ done before this time o’ day?’’” (189). Of course, the mock disapproval would be overshadowed by the elation of his sons at their father’s return.

Smith goes on to even include the family dog in his vision. “‘I’ll jest go up he path. Old Rover’ll come down the road to meet me. He won’t bark; he’ll know me, an’ he’ll come down waggin’ his tail an’ showin’ his teeth. That’s his way of laughin’” (189).

After returning home, both the passing of time and Smith’s beard growth perplex his children. “…the youngest child stood away, even after the girl had recognized her father and kissed him” (197). He then turns to his youngest son. “This baby seemed like some other woman’s child, and not the infant he had left in his wife’s arms. The war had come between him and his baby—he was only a strange man to him…” (197). This is not what Private Smith had expected at the train station. Later, his wife informs him that Rover died the previous winter.

Smith’s expectations did match the ideal he envisioned. This encapsulates the criticism that many Realists felt towards the literature of their time, leading up to their literary era. Despite the nobility of Private Smith, and his genuine longing for his family and home, his more Romantic ideals of his return are not met, and he is forced to reconcile his wishes with actuality. Many stories of Realism do not contain the “ideal” ending, but one of conflict and disappointment—just as life is.

Hamlin Garland’s story, based on his own experience of his father’s return from the Civil War, is filled with conflict and a disillusionment of ideals. Using an event that inspired the Realism movement in literature, Garland encompasses primary characteristics of the period in his story to create a more accurate understanding of the human experience after war. He achieves this by using realist notions and depictions instead of Romantic ideals.

Howells, William Dean. “The Editor’s Study.” The Heath Anthology of American Literature: Late Nineteenth Century: 1865-1910. 5th ed. Vol. C. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2006. 258-9.